One of the least known literary associations with Staffordshire, is that of Charles Kingsley’s novel Alton Locke. Tailor and Poet, which was published in 1851. The story of the rise and fall of a self-taught working man who is eventually imprisoned for rioting, is based upon a real person and a real incident. The person was the Chartist leader, Thomas Cooper, who was arrested and sentenced to two years in prison, for the events he had prompted in the Staffordshire Potteries.

Thomas Cooper was born in Leicester to a working class family and from an early age displayed a precocious intelligence, the development of which was only limited by the fact that most of his lessons were self-taught. Occasionally, he had been known to immerse himself so deeply into his studies that the sheer mental effort he put forth ended on one occasion, at least, in him being physically ill. He worked at various jobs, mostly as a teacher, lay preacher and journalist, but eventually, appalled by the conditions endured by many factory and workshop workers, he became a convinced Chartist, a member of that Victorian working class movement which supported the introduction of a People’s Charter, which called for fair representation for the working population. The Charter’s six points demanded votes for all men at 21, annual general elections, a secret ballot, constituencies regulated by size of population, the abolition of property qualifications for MP’s and the payment of MP’s. Most of these points eventually became laws of the land and form a part of the state we live in today, but none of these things came into being until the latter half of the nineteenth century, long after the Chartist movement itself had collapsed.

There were two bodies of the Chartist movement, the physical and the moral-force Chartists, who sought to bring about social change by revolutionary or evolutionary means. In his early days, Cooper was a supporter of the former faction. He was a fire and brimstone type of preacher, who like all great orators could move people with his speeches. This power comes through in Cooper’s autobiography, which is widely regarded as one of the finest working class ‘lives’ written during the Victorian age. The book, though written in Cooper’s later years after he had become a convinced moral-force Chartist, tends to carefully skate around his fiery physical-force youth and he presents himself as a far more reasonable man than he actually was in August 1842, when he arrived in the Potteries. Only by bearing in mind, that Cooper at this time advocated revolution of sorts, do the events he inspired in the Potteries make sense. Though he says in his book that he proclaimed, ‘Peace, law and order’, the resulting riots that left one man dead, dozens wounded or injured and many buildings burnt or ransacked, indicated that he said more than he was letting on.

Cooper arrived in the Potteries, after a tour of several major towns and cities in the Midlands, and here he was to make a number of speeches before moving on to Manchester. The area was in the grip of a wage dispute. In June, 300 Longton miners whose wages had been drastically cut had gone on strike. By July, the strike had expanded to all of the pits in north Staffordshire, and hundreds of miners were on the streets, begging for money, and with the pits being closed, the potteries through lack of coal, could not fire their kilns and were also closed. By early August, the dispute had attracted widespread attention, certainly the Chartists expressed sympathy for the miners’ action, but contrary to later claims that the subsequent riots were Chartist inspired, it was mostly miners and not Chartists who did the rioting. The Potteries were a powder keg, ready to explode and Cooper’s arrival, as he himself admitted was ‘the spark which kindled all into combustion’.

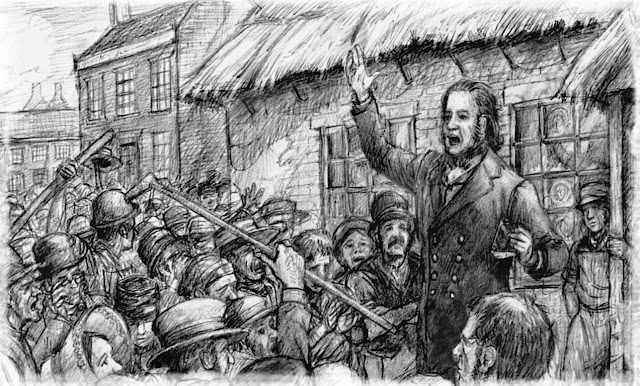

Standing on a chair in front of the Crown Inn, a low thatched building at Crown Bank in Hanley, on Sunday, 14 August, Cooper addressed a crowd of upwards of 10,000 people, delivering a brilliant Chartist speech to his audience. He look for his text the sixth commandment, ‘Thou shalt do no murder’. Throwing his net wide, he drew on examples of kings and tyrants from history, such as Alexander, Caesar and Napoleon, who had violated this commandment against their own people, even as their own government would be prepared to do. The next day, he addressed an equally sizeable crowd and moved a motion, ‘That all labour cease until the People’s Charter becomes the law of the land’.

What followed, Cooper later regretted. As the crowd dispersed. rioting started around the Potteries towns in all except Tunstall and the borough town of Newcastle. Police stations were attacked, magistrate’s houses ransacked and burned, as were Hanley Parsonage and Longton Rectory. By the 16th, the chaos had lasted a day and a night, but on that day, the most famous, or infamous incident of the uprising occurred, what is known locally as ‘the battle of Burslem’. Following the rioting in Stoke, Shelton, Hanley and Longton, a great crowd moved towards Burslem, there to meet a crowd coming from Leek. Here, though, the authorities played their hand, when a troop of mounted dragoons stopped the crowd from Leek. The magistrate in charge read the Riot Act, then tried to reason with the men, but when it was clear that they were bent on trouble, the soldiers were ordered to fire. One man from Leek was killed and many injured, the crowd was routed and the disturbances ended overnight, but for many weeks afterwards, the Potteries were full of troops and vengeful magistrates arresting rioters and Chartist leaders.

Cooper, horrified at the events he had unleashed, had tried to escape, but he was arrested and eventually tried and sentenced to two years in Stafford Gaol, on charges of arson and rioting. Here, he spent his time profitably, learning Hebrew and writing his book, The Purgatory of Suicides. On leaving prison, though, his views were found to differ considerably from the new mainstrean in Chartist thought, and he became increasingly a moral-force activist and remained so for the rest of his life.

It was in the two or three years after leaving prison, that Cooper was interviewed by the Rev. Charles Kingsley, whose Christian Socialist movement had inherited many of the Chartist beliefs. Kingsley had sought out several old Chartists and educated working men on whom he wished to base the life of the major character in the novel he was preparing. Thomas Cooper, was obviously the chief amongst these, certainly his autobiography, written many years after Kingsley had published Alton Locke, shows many striking similarities between Cooper’s life and that of his fictional alter ego. The riot that Alton inspires in the book, for which he too is committed to the prison, takes place in the countryside, amongst agricultural labourers, but behind it there is the faintest echo of the struggle in the Potteries, that one historian has considered the nearest thing to a popular revolution that the Victorian age saw.

After 1845, Thomas Cooper turned his talents mainly to writing, but he also lectured on subjects such as history, literature and photography. In this capacity, he made a number of return visits to the Potteries, to the place where on that day many years before, he had ‘caught the spirit of the oppressed and discontented’, in seeking to establish the basis of a democratic society.

Reference: Charles Kingsley, Alton Locke. Tailor and Poet (1851); Thomas Cooper, Life of Thomas Cooper, written by Himself, (1872).