In early March 1783, the local economy was in decline and people were going hungry. A poor harvest the year before plus the knock-on economic effects of the American War of Independence had caused food to become scarce and prices to rise sharply and a number of food riots broke out in Newcastle and the Potteries as a result. The most serious of these took place around the canal at Etruria and may well have been started by some of Josiah Wedgwood’s workers.

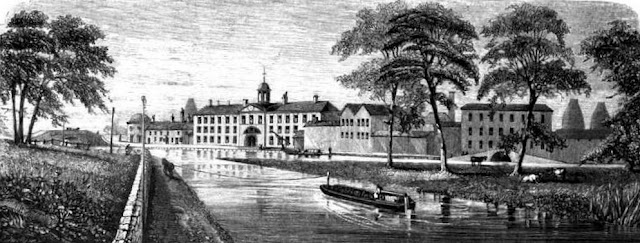

From The Life of Josiah Wedgwood (1865) by Eliza Meteyard.

There had been some trouble in Newcastle for several days and the rioters there seem to have joined or inspired the riot that broke out at Etruria on Friday 7 March. The trouble started when a barge carrying much-needed supplies of cheese and flour moored up at Etruria where the food was to be off-loaded before being distributed around the Potteries. However, at the last moment the barge’s owners decided to send the boat on to Manchester. Within a short time of this decision shop owners in Hanley and Shelton heard the news and they in turn informed their angry customers. They had probably heard about the barge’s departure from some of Wedgwood’s own workers, certainly that suspicion was voiced in a letter written by Josiah Wedgwood junior, son of the famous potter. Later that same day Josiah junior wrote to his father (who was then in London on business) describing how when the news spread about the departing barge, several hundred men women and children had quickly gathered and chased after it along the canal, finally catching up with it at Longport. Believing that the boat had been sent away to increase the scarcity of provisions and thus up the prices even more, the crowd were in a black mood and not to be trifled with, so when they found that the bargee would not pull the boat over one of the crowd leapt aboard to tackle him. The boatman immediately cut the tow rope and slashed at the man with his knife and voices from the crowd on the towpath called out “Put him in the canal.” A ducking may well have been the man’s fate had not another bargee come to his rescue and he had been able to escape onto another craft, albeit leaving his own barge in the hands of the mob as he did so.

The captured boat was then hauled it back to Etruria in triumph and by late afternoon was tied up alongside Wedgwood’s Etruria works where the crowd unloaded the cargo into the factory’s crate shop. Most of the rioters then went home meaning to return the next day for distribution of the goods. In the meantime a few men were set as guards. At about 7.30 that evening four of these sauntered up to Etruria Hall and asked for something to eat and drink while they were on watch. Another of the Wedgwood children, Josiah’s older brother, 17 year old John went to them and stood talking with them for a time then too did their mother Sarah Wedgwood, who also spoke with them for a while before the men went off. The nervousness of the Wedgwood household at this point is, evident in young Josiah’s hasty missive to his father, but the family were not bothered any further that evening and at breakfast the next day things were still quiet.

On the Saturday morning the crowd gathered back at the canal side and some of the goods seized the day before were sold off at what were considered by the crowd to be more reasonable prices. One of the letters states that this was at two-thirds the normal price, while sometimes the goods were given away. The meagre proceeds were then handed over to the disgruntled owners of the captive barge. The authorities meanwhile had taken steps to deal with the rioters. An express message had been sent to Lichfield asking for some companies of the Staffordshire Militia to come to their aid. Closer at hand, though, were a company of the Carmarthen Militia who that day had arrived in Newcastle on their way back to Wales. Due to the troubles in Newcastle itself and now in Etruria, the commanding officer was asked if he could help in dealing with the rioters. He agreed, and the force put itself at the disposal of the local magistrates who now had the job of quelling the disturbances.

Some justices went to meet with the mob still gathered around the captured boat, but the Militia were kept at a distance while the officials tried to settle matters peacefully. Here the letters are at odds with one another, one stating that all efforts to get the mob to disperse, including getting the master potters (whose workers formed the bulk of the mob) to try and influence them, but to no avail, while the other letter states that the magistrates’ efforts were a success and that the mob agreed to leave, providing the boat was left where it was. Judging by the fact that several days later the mob was demanding the return of the boat the latter seems the most likely state of affairs, but the details still remain confused.

Nothing of great significance seems to have happened on the Sunday, though some of the local manufacturers and officials held a crisis meeting at Newcastle to discuss how best to calm the situation down and deal with the mob. A subscription was entered into perhaps to placate the rioters, Josiah Wedgwood’s son John was present at the meeting and donated £10 to the fund. But after the quiet Sunday, Monday saw a return to the stand-off of previous days as the mob gathered at Etruria once more. This time they were in a far more bullish mood and sent messengers to the magistrates outlining their demands, namely to have the boat delivered back to them and its contents sold there.

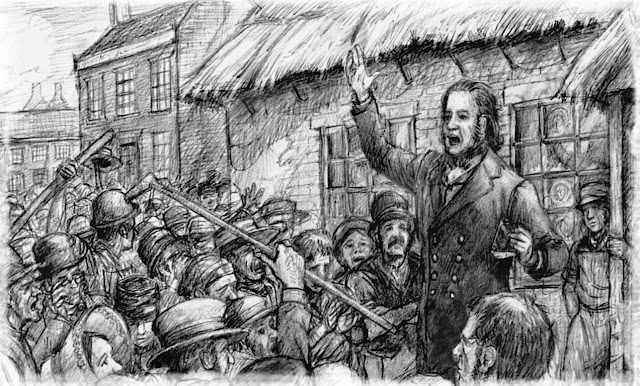

After a quiet Sunday, Monday saw a return to the stand-off as the mob gathered once more, this time outside Billington’s (probably the premises of Richard Billington, who carted coals for Wedgwood and rented 38 acres of the Etruria estate), where there was a meeting of the master potters and several officials. These included John Wedgwood in his father’s stead, Dr Falkener of Lichfield, Mr Ing and Mr John Sneyd of Belmont (a neighbour of the Wedgwoods), who harangued the mob on their bad behaviour and the detrimental effect it would have on the price of corn, as too did John Wedgwood and Major Walter Sneyd of the Staffordshire Militia. The latter was there at the head of a detachment of the Staffordshire Militia, who stood by ready if needed. The masters and officials though still hoped that the rioters would listen to reason and a generous subscription was again raised, John Wedgwood giving £20 this time. The mob, though, did not accept this graciously remarking caustically that the money would not have been provided had they not caused trouble and made the manufacturers sit up and pay attention. They continued calling for the boat to be returned to them and the corn to be sold on fairly. Their demands became so loud and threatening that the Riot Act was read out and the mob was told that if they did not disperse to their homes in an hour’s time, that the Militia would be ordered to fire on them. The crowd, though, were defiant, jeering that the militia men dared not fire on them and that if they did then the rioters would attack and destroy Keele Hall, the ancestral home of the Sneyd family of Major Sneyd was the current heir. According to some accounts the rioters also put their women and children at the front confident that the soldiers could not fire on them.

Despite this, after the hour had passed, the chief magistrate Dr Falkener was apparently on the verge of ordering the nervous militiamen to fire, when two of the rioters accidently fell down and made him pause and consider his actions. One of the Sneyds, huzzaring as he did so, got about 30 of the men to follow him, intending perhaps to charge the mob, but his effort was thwarted by women in the crowd who called out, “Nay, nay, that wunna do, that wunna do.” and embarrassed by the mocking cries the militiamen baulked, turned back and left the crowd alone. Unable or unwilling to take firm action, the officials agreed that the corn taken in the boat should be sold on at a fair price. And for now that was that and the crowd had their way. The magistrates, though, were now determined to make the leaders of the riot pay for the trouble they had caused and to bring the disturbances to an end once and for all.

Two of the ringleaders of the mob had been quickly identified as Stephen Barlow and Joseph Boulton. According to report, Barlow was born in Hanley Green, was aged about 38 and seems to have had a chequered history prior to the riots, having apparently served in the Staffordshire Militia, but had been drummed out for bad behaviour. He may also have had previous with the law as records show that four years earlier at the Epiphany Assizes at Stafford of 1779, one Stephen Barlow was in court for some unspecified crime he had committed in Penkridge. At some point he had married and by 1783 was the father of four small children and was living in Etruria. The authorities certainly knew where to look for him and that night after the riot, magistrates and constables converged on his house. On hearing the men at the door, Barlow quit his bed naked and attempted to escape by climbing up the chimney. He probably would have got away except that in his haste he dislodged some bricks and when his pursuers came out to see what was happening they caught sight of him hiding on the roof behind the chimney stack. When he was brought down, Barlow refused to get dressed and though it was a cold night suffered himself to be transported stark naked all the way from Etruria to Newcastle. After subsequently being taken to Stafford Gaol, Stephen Barlow was held there until his trial.

So too was Joseph Boulton, but he remains a shadowy figure in this drama as nothing seems to be known of his background. Beyond noting that two ringleaders had been captured at home that night and sent to Stafford gaol, his name was not mentioned in contemporary newspapers, though John Wedgwood who was at Stafford to witness the trial wrote to his father in London and noted that the man had been acquitted by the court. Stephen Barlow, on the other hand was not so lucky. The judge in summing up at the trial on 15 March, detailed Barlow’s offence and laid out the law regarding riots in the clear and clinical manner of the Riot Act. “That all persons to the number of twelve or more, who remain in any place in a tumultuous manner after proclamation has been made for the space of one hour, subject themselves to an indictment for capital felony.” In other words, the death sentence.

The message this sent out was clear, namely those hundreds who had assembled and been involved in the rioting on 10 March, most of whom had since either fled the area or had thus far escaped detection, were just as guilty as Barlow and could expect the same treatment if caught and convicted. Barlow meanwhile was sentenced to death without a quibble and on Monday 17 March 1783, exactly a week after the riot, at Sandyford near Stafford, he was escorted to the gallows by a body of militia and there he was hung by the neck until he was dead. His body was then returned to the Potteries and buried locally two days later.

It had been a startlingly quick chain of events which did indeed have the desired effect quelling any further disturbances, but it perhaps shocked many law-abiding citizens too, disturbed by such arbitrary use of the law. Looking back from over half a century later even local historian John Ward – who as a solicitor and witness to the Pottery Riots of 1842 had very little sympathy with rioters – seems to have been taken aback by this blatant show trial. Writing about Stephen Barlow, he noted that he ‘became a victim rather to the public safety, than to the heinousness of his crime.’ According to some accounts Barlow was not the only victim, as more than one paper reported briefly that following the execution, Barlow’s wife hung herself in despair.

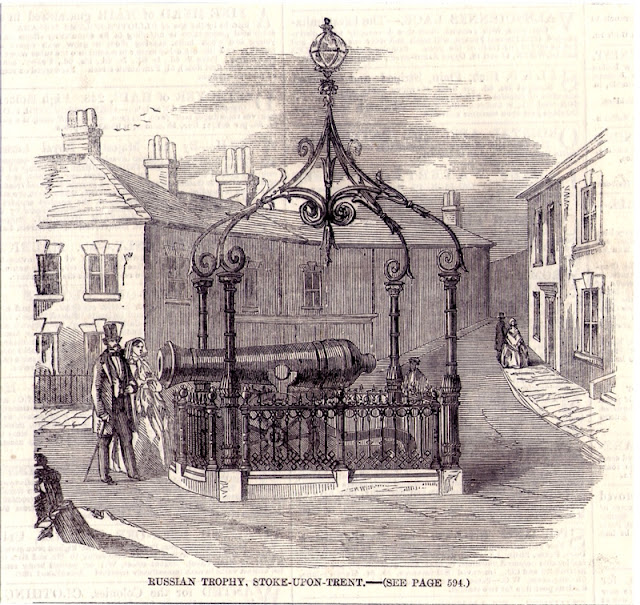

Reference: John Ward, The Borough of Stoke-Upon-Trent, pp. 445-446; Ann Finer and George Savage (Eds.), The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood p.268: Correspondence of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol. 3, pp. 8-9; Derby Mercury, Thursday 13 March 1783, p.3; Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser, Tuesday 25 March 1783, p.3; Manchester Mercury, Tuesday 25 March 1783, p.1; Kentish Gazette, Saturday 29 March 1783, p.3; Northampton Mercury, Monday 24 March 1783, p.3; Stamford Mercury, Thursday 27 March 1783, p.2; Ipswich Journal, Saturday 22 March 1783, p.1; Hereford Journal, Thursday 3 April 1783, p.3.