When he paid a visit to the Potteries in the summer of 1874, journalist James Greenwood noted that Hanley was a town full of dogs:

‘Tykes of all ages, sizes, and complexions sprawl over the pavements, and lounge at the thresholds of doors, and sit at the windows, quite at their ease, with their heads reposing on the window-sill, hob-and-nob with their biped “pal,” who cuddles his four-footed friend lovingly round the neck with one arm, while his as yet unwashed mining face, black and white in patches as the dog’s is, beams with that satisfaction which content and pleasant companionship alone can give.’

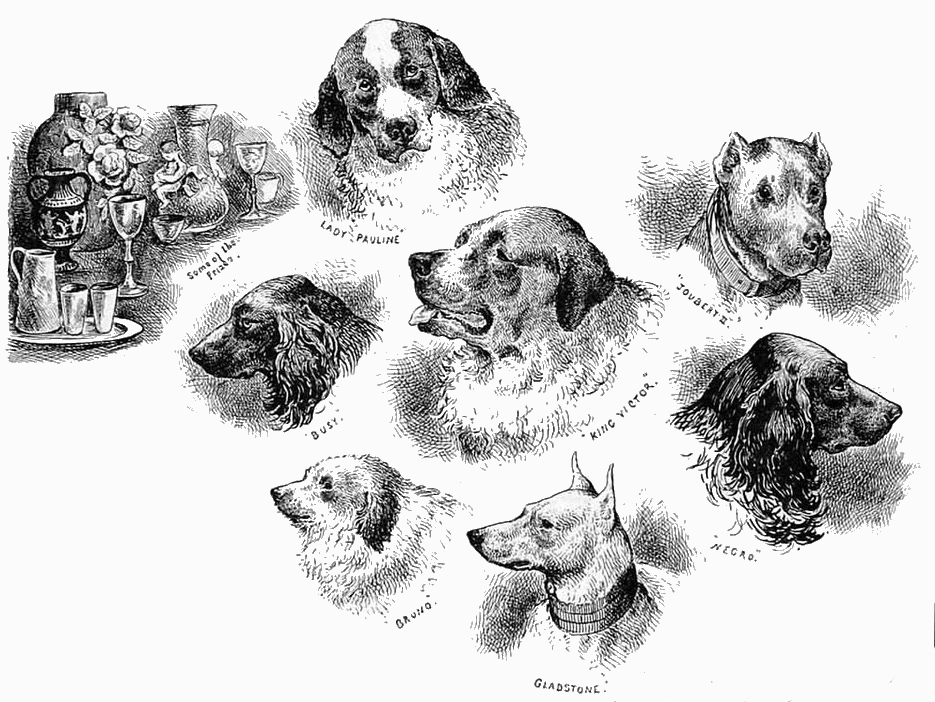

How accurate a portrait of the town this was is open to debate as Greenwood immediately went on to write the infamous story of the ‘man and dog fight’ that scandalised the area, a tale that ultimately backfired on him when it became pretty obvious that he had concocted the whole story. Yet there is plenty of evidence to suggest at least in the comment above that Greenwood was not being untruthful and the locals were indeed keen pet owners and dog fanciers. A dog and poultry show was regularly held in Hanley from 1865 into the 1870s and in October 1883 Hanley hosted a major dog show organised by the North Staffordshire Kennel Club. This proved so successful that in February 1885 a second exhibition took place. This was larger and much more widely reviewed by the press, attracting not only local but national and even international attention.

Held over two days 24th and 25th February in the old covered market in Hanley, there were 774 entries for the show and there could have been more but for a lack of space. Most of the major show breeds were present in large numbers. There were 170 fox terriers; 74 St Bernards; 27 mastiffs; 22 pointers; 18 setters; 88 collies; 34 bull dogs; 20 bull terriers; 48 dachshunds; 18 pugs; and six bloodhounds. Add to this the more obscure dogs and hounds, some from abroad, plus some champion dogs including five mastiffs who had secured honours at the prestigious Crystal Palace shows, and you had you had a major treat for dog lovers from across Britain. Anticipating a good turnout both the North Staffordshire and London and North Western Railways issued cheap tickets for those wanting to attend the show.

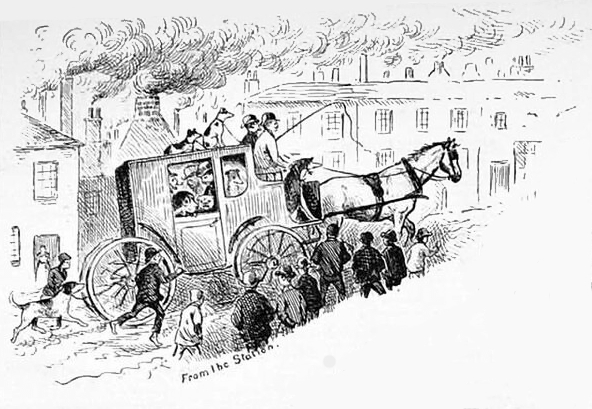

Providing a series of illustrations for The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, was Louis Wain, the artist who in later life went mad and spent his latter years painting numerous pictures of sinister anthropomorphic cats. At the time of the Hanley dog show, however, he was still quite sane and penned a series of fine dog portraits and whimsical side illustrations. The most amusing sketch showed a carriage trundling its way up the bank from Stoke Station up into Hanley, bringing with it a fine collection of prize pooches, large and small, riding in or on top, or running behind the coach, evidently much to the astonishment of onlookers.

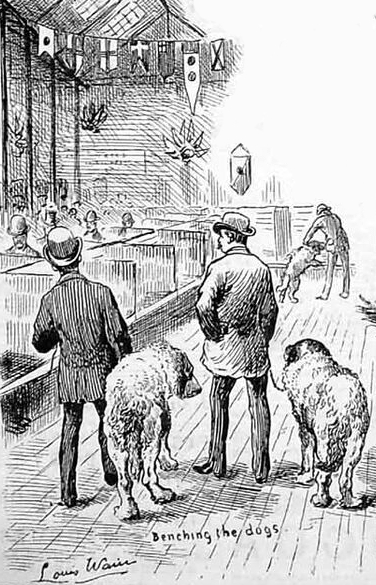

Another of Wain’s illustrations showed that once in the market hall the various dogs were housed in a series of pens ready for the viewing of the general public and while they waited on the judges to do their rounds. There were a few problems. A reviewer in the same paper that carried Wain’s illustrations noted that quite a few of the dogs on show still bore evidence of a mange epidemic that had recently swept the country. Most were over the disease and the worst effects they showed were rather patchy coats, but a few displayed signs that their condition was still ‘alive’, much to the reviewer’s alarm. The entry of such obviously infected dogs he put down to the laxness of the ‘honorary veterinary surgeon’ and the inconsiderate nature of some owners. This was all the more surprising as one of the Kennel Club’s rules stated quite forcefully that no dog suffering from mange or any other infectious disease would be allowed to compete or be entitled to receive a prize.

The writer also suggested that the chains holding the dogs in their pens were in many cases far too long. Some of the dogs were fierce or excitable and in their frenzy apt to fall over the edge of their bench and with the smaller dogs in danger of hanging themselves. Wain illustrated the point with a picture showing a placid St Bernard face to face with a group of irate terriers, one of whom had taken just such a tumble and was in danger of throttling itself. The long chains also allowed more mischief as some of the animals were able to get around the partitions and engage in scraps with their surprised neighbours.

In the long run, though, these were minor issues in what turned out to be a very successful and well organised show. And as can be seen from Louis Wain’s fine illustrations, despite the ravages of the mange epidemic there were still many handsome dogs on hand to pick up the numerous prizes. So popular did the exhibition prove that another show was organised early the next year and the competition carried on through the latter years of the 19th century expanding into a dog and cat show by the late 1890s.

References: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 7 March 1885 pp. 607, 617, 623. James Greenwood, Low Life Deeps, pp. 16-17

Pictures: Author’s collection.