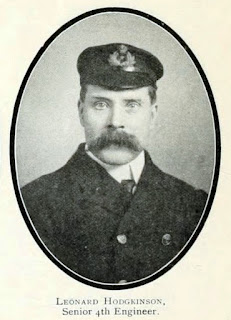

Stoke-on-Trent’s best known connection with the Titanic disaster is of course the ship’s venerable skipper, Captain E. J. Smith, but a less well-known Potteries-born sailor who also perished in the Titanic disaster was Senior Fourth Engineer Leonard Hodgkinson. At the time of his death he was 46 years old, and like Captain Smith had spent most of his adult life at sea, albeit in a far different environment to that of his much more famous shipmate. As a member of the ship’s engineering staff, his working life was one spent for the most part in noisy, hot engine rooms, with little view of sea or sky save when he was off duty.

Leonard was born at 20 North Street, Stoke-upon-Trent, on 20 February 1866, the second son and fifth child of potter’s presser John Hodgkinson and his wife Caroline nee Steele. Educated at St Thomas’ School, Stoke, before the age of 15, Leonard was apprenticed as an engine fitter with Messrs Hartley, Arnoux and Fanning, in Stoke. Once his apprenticeship was done, Leonard left the Potteries sometime in the 1880’s and took up a position with Messrs Lairds of Birkenhead, lodging with his elder sister Rose, her husband Henry Mulligan and their children, who had settled in Liverpool sometime after their marriage in 1877. It was in Liverpool that Leonard met his wife-to-be, Sarah Clarke. The couple were married in West Derby, Liverpool on 14 February 1891 and within a few years the couple had three children.

Leonard was now a seagoing marine engineer. He served for five years with the Beaver Line, whose ships sailed from Liverpool to Quebec and Montreal. In 1894, though, the Beaver Line went into liquidation and it may have been at this point that Leonard left and joined Rankin, Gilmour and Co., Ltd, which firm he also served with for five years, earning his first class certificate in the process. He may also have served with the Saint Line of ships which were owned by Rankin and Co., most of which carried the ‘Saint -’ title. Leonard’s final position with the company was as chief engineer aboard a ship with just such a title, the Saint Jerome.

For a few years between 1901 and 1905, Leonard quit the sea and set himself up in business ashore as a mechanical engineer, but in May 1905, he returned to his old line of work, joining the White Star Line, serving first as assistant engineer on the Celtic, later earning promotion to fourth and then third engineer.

According to family lore, Leonard Hodgkinson was keen to serve on as many vessels as possible before retirement, so was doubtless pleased after what appears to have been a six year stint aboard the Celtic, to be transferred over to the glamorous new Olympic (the Titanic’s elder sister) when that ship came on-line in June 1911. Here he was briefly bumped back down to assistant engineer, but soon earned promotion to fourth engineer once again. Perhaps more troublesome for him and his family was the fact that the Olympic was to sail from Southampton. There is no indication that the whole Hodgkinson family moved to Southampton at this time, though it is a possibility, but if not, then Leonard had to put up at lodgings in between journeys and perhaps only got to see his family on a few occasions when he could make the journey back to Liverpool.

It was in early 1912, that Leonard travelled to Belfast where he joined the staff under Chief Engineer Joseph Bell, who were involved in getting the Olympic’s younger sister Titanic up and running. On 2 April he was signed onto the ship’s books for the delivery trip from Belfast to Southampton and on 6 April he was signed on once again in Southampton, now as senior fourth engineer.

As senior fourth engineer, Leonard Hodgkinson was the highest ranking of the five fourth engineers aboard the Titanic, one of whom was a specialist in charge of the ship’s refrigeration equipment. Whilst at sea their duties involved checking that the adjustments and routine maintenance of the ship’s machinery were carried out. They dealt with any minor problems as they arose, answered any orders rung down via the ship’s telegraphs and ensured that everything ran as smoothly as possible. As officers it was also their duty to supervise the firemen, trimmers and greasers who worked with them down in the bowels of the ship.

How Leonard’s days passed aboard the Titanic prior to its fateful collision is unknown, as too are his deeds on the night in question, as no accounts seem to exist noting him. If the story is to be believed, though, his fate and that of the 1500 other people who perished on the Titanic was foreseen by one of his relatives back in the Potteries, none of whom had any idea that Leonard was aboard the Titanic. According to the story she later told, two days before the disaster, Leonard’s 14 year old niece, Rose May Timmis, the daughter of Leonard’s elder sister Agnes, was sleeping in the same bed as her grandmother Caroline Hodgkinson (Leonard’s mother) when she had a nightmare. Rose dreamt that she was standing by a road in Trentham Park looking out over the lake, when a large ship steamed into sight. Suddenly the ship went down at one end and she could hear screams. Rose herself woke up with a yell that frightened her grandmother awake. When the frightened girl related her dream her grandmother snapped, “No more suppers for you, lady; dreams are a pack of daft.”

After a while, Rose drifted back to sleep once more, only to find herself dreaming the same scene and as before when she heard the people screaming she did the same. She recalled that her grandmother was furious with her this time. A few days later, though, the news of the disaster broke and the family learnt that Leonard had been aboard the Titanic and that he and the other 34 engineering officers aboard had perished with the ship. Though several bodies from the engineering department were recovered in the following weeks, Leonard’s was not one of them.

Though Leonard’s body was never found, he is remembered in several memorials, most notably on the Engineers Memorial, East Park, Southampton, the Titanic and Engineers memorial, Liverpool; the Glasgow Institute of Marine Engineers memorial; and the Institute of Marine Engineers Memorial in London. There is also a brass memorial plaque in the church of St Faithful, in Crosby, Liverpool, dedicated to the memory of the Chief Engineer and his Engine Room staff.

Leonard Hodgkinson was not the only member of his family to go to sea. His son Leonard Stanley also became a marine engineer with White Star and later Cunard. He served on the transatlantic run most of his career, mainly on RMS Majestic before the war and later on the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth.

Website: Encyclopedia Titanica