Illustration by W. H. Overend.

Smith Child, later an admiral in the Royal Navy, who also dabbled locally in the pottery industry, was born at the family seat of Boyles Hall, Audley in early 1729, and baptised in the local church on 15 May that year. He was the eldest son of Smith Child of Audley and the wealthy heiress Mary nee Baddeley, whose family had a long Staffordshire pedigree. The Childs by contrast were originally a Worcestershire family, one branch of which had migrated to North Staffordshire, settling in Audley. They had once possessed considerable property, but most of this had been lost by the future admiral’s father, whom local historian John Ward described as ‘a man of polished manners, but wasteful in his habits’. His marriage to Mary Baddeley was therefore quite a coup by which his family inherited several of the Baddeley estates that his eldest boy, Smith, would inherit.

Enjoying the patronage of the politician Earl Gower as well as Vice-Admiral Lord George Anson, young Smith Child was entered the navy in 1747, serving aboard HMS Chester under Captain Sir Richard Spry. He was commissioned lieutenant on 7 November 1755 whilst serving in the Mediterranean aboard the Unicorn under Captain Matthew Buckle, and returned home to become a junior lieutenant aboard the ancient Nore guardship Princess Royal commanded by Captain Richard Collins. He served as a lieutenant on several more ships during the Seven Years War seeing action aboard the 3rd rate HMS Devonshire at the siege of Louisbourg in North America in 1758, then on the much smaller frigate HMS Kennington. Child is said to have also seen service the siege of Pondicherry, India, during 1760-1761.

After the war ended in 1763, like many officers Lieutenant Child returned home and from this point in his life that he settled down in the Potteries. He erected a large pottery factory in Tunstall, that between 1763-1790 produced a range of earthenware goods. The following year he married Margaret Roylance of Newfield, Staffordshire, acquiring a significant estate from her family. Initially he lived with his wife at Newcastle-Under-Lyme, but the following year he inherited his uncle’s seat, Newfield Hall, Tunstall, a large three-storey house with a five-bay entrance front and seven-bay side elevation, that enjoyed impressive views over much of the Potteries. In 1770, he moved into the hall rebuilding it and in his time on shore cultivated a keen interest in agricultural and other useful pursuits. Here the Childs lived a happy life and raised their five sons: Thomas, who as a midshipman was drowned at sea in 1782; John George whose son later became heir to the family estates; Smith who died without children; and Roylance and Baddeley, whose names recalled their most recent family history. But it was a short interlude in his naval career as at the beginning of what became the American War of Independence in 1775, Smith Child was recalled into service and early in 1777, was sent to take command of the hospital ship Nightingale in the Thames. Later that year he was promoted commander of the store ship HMS Pacific on 30 October 1777, taking the ship out to North America in the summer of 1778.

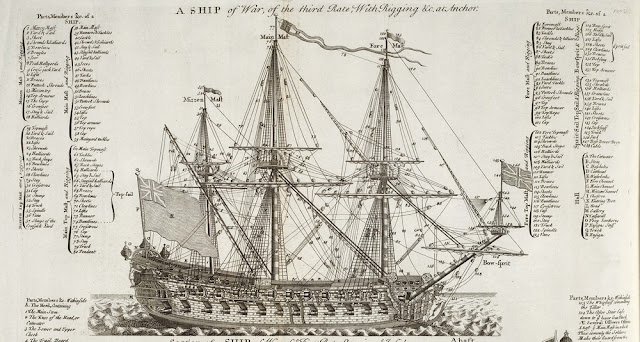

He was posted captain on 15 May 1780, taking temporary command of the Raisonnable, but in August 1780 in the most important move of his career, Captain Child was given command of the 64-gun HMS Europe and took part in two important sea battles for the control of the strategic Chesapeake Bay. His enemies here would not be American sailors (the American rebels barely possessed a navy), but the French, who had weighed in heavily on side of the Americans, effectively funding and supplying the rebellion in retaliation for the defeat and loss of Canada to Britain in the Seven Years War. As part of Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot’s fleet, Child participated in the Battle of Cape Henry on 16 March in which the British fought off a French fleet attempting to enter the Bay. Positioned in the vanguard of Arbuthnot’s fleet, Europe was one of three ships left exposed by the admiral’s poor tactics, losing eight crewmen killed and 19 wounded to the punishing French bombardment. The British won this round despite their casualties, but the vital waterway would be the scene of one more dramatic fight.

This was the Battle of Chesapeake Bay, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes, fought against a slightly larger French fleet on 5 September 1781, when HMS Europe along with the 74-gun HMS Montagu, formed the leading part of the centre division of Admiral Sir Thomas Graves’ fleet, and was heavily involved in the fighting that ensued. These two ships suffered considerable damage in the intense two-hour battle. Child’s report after the battle lists numerous masts and spars damaged or shot through, twelve shots struck the hull while there was much damage to the upper works, including splintered decking and fife rails at the base of the masts broken to bits; the rigging and shrouds were also badly cut up and three gun carriages had been damaged, one beyond repair. Europe had taken a pounding, ‘the ship strains and makes water’ Child’s report noted. There was a human cost too, nine members of her crew were killed in the action, and a further 18 wounded.

Outgunned and battered by the encounter, the British fleet eventually withdrew from the action, finally losing control of the bay and the ability to keep their ground troops supplied with food and ammunition. This sorry state of affairs soon after resulted in the Franco-American victory at Yorktown, the knock-on effect of which saw the withdrawal of British forces from the war and Britain’s eventual recognition of the newly-founded United States of America. This outcome was no discredit to Smith Child, though, who had fought well and his standing in the navy enabled him to obtain preferment for most of Europe’s officers when the ship returned home and was paid off in March 1782.

Peace was declared in 1783 and for the next six years Smith Child served at home. However, on the continent, more trouble was brewing when in 1789 the French Revolution broke out across the channel. Though confined to France, the bloody revolution would be the catalyst for a renewed bout of Anglo-French rivalry that started in 1792, when after defeating an invading Prussian led army at Valmy, the new French Republic launched an invasion of the Netherlands. The next year the deposed French King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were executed which caused outrage amongst the royal families and governments of Europe and brought Britain into the coalition that had formed to defeat the Republic. With a new war to fight, the Royal Navy – now a much fitter beast than during the American war – was again expanding and called in many of its old officers to fill in the gaps; this included Smith Child.

After serving for some time in the Impress Service at Liverpool, in November 1795, Smith Child was given command of the HMS Commerce de Marseille, a huge French-built ship that had been surrendered to the Royal Navy in the 1793 Siege of Toulon. The ship, originally a 118-gun three-decker, at first seemed well built like most French vessels and an early report stated that she sailed as well as a frigate, but her construction gave the ship an unacceptably deep draft while her internal framing was found to be inadequate for the high seas and the hull suffered serious strain when sailing. Deemed unworthy of a major overhaul, the vessel had been quickly downgraded and remained languishing at anchor at Spithead until the autumn of 1795. She then underwent a partial repair, and was armed and equipped for sea. Shortly afterwards, however, the guns on her first and second decks were sent on shore again, the redundant gun ports were sealed up and she was converted to a store and transport ship. The ship was then loaded with 1,000 men and stores for transport, drawing a whopping 29 feet when fully laden. The ship was tasked as part of a large convoy of some 200 transports escorted by 8 ships of the line under Rear Admiral Christian, that was supposedly on a secret mission to the West Indies that would soon become much less secret after the disaster awaiting it off shore.

Child’s ship was in poor condition before sailing and she was damaged beyond repair when shortly after the fleet had set out, on 17 and 18 November the English Channel was struck by a violent storm of nigh on hurricane strength. This sent Admiral Christian and his escort squadron running to Spithead for cover while the transport fleet was scattered, some sinking, others being driven ashore and wrecked. Some two hundred bodies were washed ashore after the storm and the fleet was left so disordered that it was not ready to make another attempt until early December, which was again battered by a fearsome storm. The Commerce de Marseille, though, would not be among them, because as a result of the first storm, ‘… this castle of a store-ship was driven back to Portsmouth; and, from the rickety state of her upper-works, and the great weight of her lading, it was considered a miracle that she escaped foundering. The Commerce-de-Marseille re-landed her immense cargo, and never went out of harbour again.’

Child had commanded his last ship and after such a clunker he was perhaps glad of it. He was promoted to Rear Admiral on 14 February 1799, but it was a nominal rank and he apparently saw no further sea service. Subsequently promoted to Vice Admiral on 23 April 1804, and Admiral of the Blue (the junior position in the rank of full admiral) on 31 July 1810.

At home, as well as being a noted pottery manufacturer, Admiral Child served at times as a Justice of the Peace for Staffordshire, a Deputy-Lieutenant of the county, and was a highly respected member of the local landed aristocracy. He died of gout of the stomach on 21 January 1813 at Newfield aged 84, and was buried in St. Margaret’s Church, Wolstanton, under a plain tombstone. His son and heir John had died two years previously, so Smith Child’s estate passed to his five year-old grandson who would later become the Conservative M.P, and noted philanthropist Sir Smith Child.

Reference: The Graves Papers and Other Documents Relating to the Naval Operations of the Yorktown Campaign, July to October 1781, (New York, 1916) p. 67 and p.73. William James, The Naval History of Great Britain, Vol.1 (London, 1837), p.253. John Ward, The Borough of Stoke-Upon-Trent (1843) pp. 85-86.