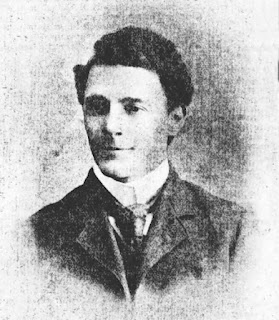

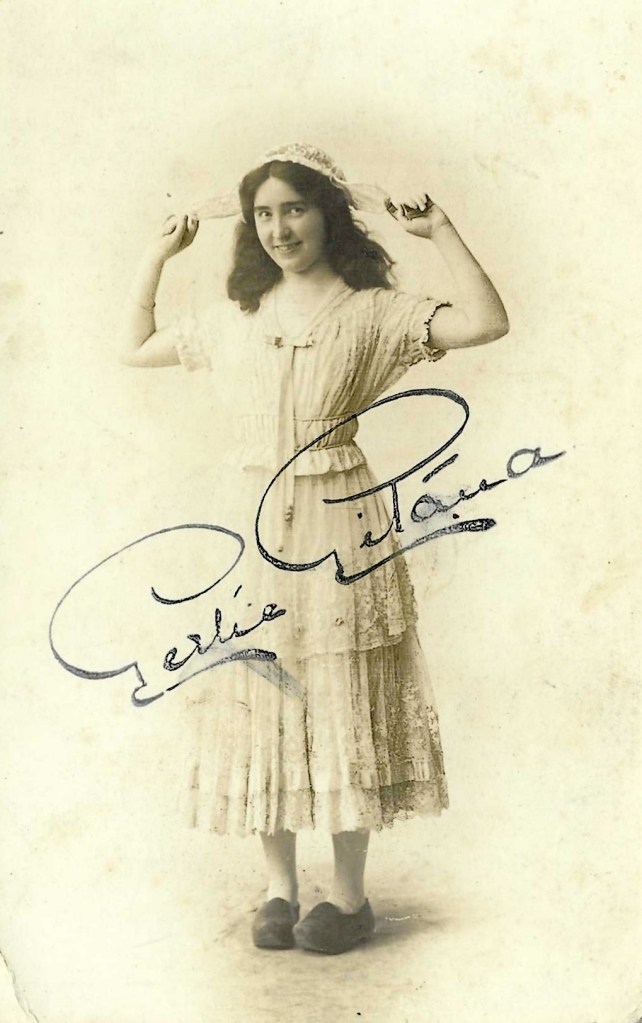

Of all the famous names who have hailed from the Potteries, few in their lifetime gave more honest, unalloyed pleasure than Gertrude Astbury, who as ‘Gertie Gitana’ became a darling of the music halls prior to World War One. Her talent and staying power were considerable. In her prime, her name on the bill was enough to ensure a full house, and even in the twilight years of her career, she was still able to command a large audience.

Gertrude Mary Astbury, the eldest child of pottery turner William Astbury and Lavinia nee Kilkenny, a teacher at St Peter’s R. C. School in Cobridge, was born on 28 December 1887 at 7 Shirley Street, Longport, but the family lived at various addresses after that. When in 1954 the City Council decided to rename Frederick Street, behind the Theatre Royal in Hanley, as Gitana Street in her honour, Gertie wrote a letter to The Sentinel saying that she was very proud of the honour noting that ‘Gitana-street is adjacent to the theatre stage is appropriate.’ She then added, ‘I don’t think anyone knows of it, but it may be of some slight interest to mention that I actually lived in Frederick-street; my mother had a small shop there. I was three years old when we moved there and we were there for two or three years.’ There is no official evidence to support this story, but at the time of the 1891 census, Gertie was certainly living with her grandparents in Bucknall New Road, Hanley, while her parents and brother James lived in Burslem. Perhaps the family moved to Fredrick Street after the census was taken?

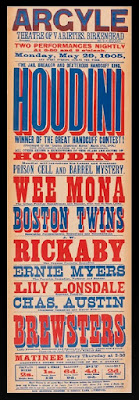

From a very early age, Gertie proved to be something of a musical prodigy. Apparently as a toddler she delighted in putting on performances for her dolls and by the age of four she had been enrolled into Thomas Tomkinson’s Gypsy Children as a male impersonator, singer and comedienne and was soon earning star billing as ‘Little Gitana’ (the Spanish word for a female gypsy). The tale told of her discovery is that she was seen dancing in the street (arguably in Frederick Street, Hanley) by two girls attached to the troupe who befriended her. She then went along to one of the rehearsals and began copying the moves. Thomas Tomkinson noticed her and recognising her ability, applied to her parents to let her join the troupe. Once in the line-up and out touring with the show first around the Potteries, then through Wales, Gertie honed her skills and there was no doubting her burgeoning talent and her performances were regularly singled out for praise in press reports. In 1896, her career was given a helping hand by two music hall veterans, James and Mabel Wignall, known professionally as Jim and Belle O’Connor, who took her away from the Gypsy Children and under their wing. Though the O’Connors were apparently somewhat protective of their young charge, it was not in any sinister way and Gertie always referred to them affectionately as ‘Uncle and Auntie.’ It was thanks to them that at only eight years of age, Gertie made her music hall debut at the Tivoli in Barrow-in-Furnace, where she sang the song, ‘Dolly at Home.’ Two years later at the age of ten, she had a major billing at The Argyle in Birkenhead, and her first London appearance came in 1900.

By the age of 15, Gertie was earning over £100 per week, much more than her father earned in a year. At the age of 17, she topped the bill for the first time at The Ardwick Empire at Manchester. From late 1903 onwards, though often still appearing as Little Gitana, she was also being referred to increasingly as Gertie Gitana, the stage name she would adopt for the rest of her career. As she grew into womanhood, though, her skills and repertoire expanded and as well as singing she entertained by tap dancing, yodelling, and playing the saxophone, a relatively new instrument developed in the States and which at that time was something of a novelty in Britain. Her music hall repertoire of songs over her career included ‘All in a Row’, ‘A Schoolgirl’s Holiday’, ‘We’ve been chums for fifty years’, ‘When the Harvest Moon is Shining’, ‘Silver Bell’, ‘Queen of the Cannibal Isles’, ‘You do Look Well in Your Old Dutch Bonnet’, ‘Never Mind’, ‘When I see the Lovelight Gleaming’, and most famously ‘Nellie Dean’ which she first sang in 1907. It was a song her younger brother James had heard in the United States and was an instant success for Gertie, becoming her signature tune. Her first gramophone recordings, dating from 1911–1913 (some of which can be heard online), were made in London on the Jumbo label.

During the Great War, like many music hall performers Gertie turned her talents to entertaining the war wounded in hospitals or raising funds for the injured and she gained a following with the men in the trenches as a forces sweetheart. After the war, she appeared in pantomime, most notably as the principal boy in Puss in Boots, or as Little Red Riding Hood, and Cinderella. One amusing incongruous tale from this period is that she was reputed to have said the line in Cinderella, ‘Here I sit, all alone, I think I’ll play my saxophone’, before removing the instrument from the stage chimney and bashing out a tune*. Two musical shows were specially written for her: Nellie Dean and Dear Louise, and in 1928, despite initial opposition from the O’Connors, Gertie married her leading man in the latter, dancer Don Ross. Don was as ambitious and driven as his wife and would later prove to be quite the impresario, bringing over one of the first Vaudeville strip-tease artists after a visit to the States, running a three-ring circus and organising variety shows; he later became King Rat of the Grand Order of Water Rats and founder and first president of the British Music Hall Society.

After the shows had run their course, Gertie returned to the variety scene, working for some time in partnership with blackface performer G. H. Elliott and an up-and-coming comedian Ted Ray, who liked her immensely. In his autobiography, Ray described both Elliott and Gertie as charming and courteous professionals, who never let their acts devolve into smut and no matter what their moods or what else was going on in their lives, never let an audience down or turned in a sub-par performance.

However, determined to retire at 50, by her own design Gertie’s career was now winding down. Made rich by her tireless work over the years (“No gutters for Gertie.” she sometimes commented wryly on her wealth) she was able to retire in 1938, but the old trouper could not be kept down and ten years later she made a short but very successful comeback with other old music hall stars in the show Thanks for the Memory produced by her husband. The show was the centrepiece of the Royal Command Performance in 1948. Her final appearance was on 2 December 1950 at the Empress Theatre, Brixton. She retired completely after that and spent her remaining years quietly, though she increased her fortune by speculating successfully on the stock market. On her death she left just over £23,584 in her will, equivalent to £484,727.62 in 2024.

Gertrude Ross, nee Astbury, alias Gertie Gitana, died of cancer on 5 January 1957 in Hampstead, London, aged 69, and was buried in Wigston Cemetery, Wigston Magna, Leicestershire, where her husband had been born. Some lines from her most famous song, ‘Nellie Dean’ are engraved on the gravestone.

By all reports, Gertie, though no pushover after years toughing it in showbiz, was an incredibly good natured and generous woman, well-liked not only by her legion of fans, but also by her fellow performers who felt her loss. After her death her friend, comedian Ted Ray, wrote ‘She was the most gentle, loveable person I ever met… A perfect artiste in every sense of the word. I place her among the immortals.’ In his book My Old Man, former Prime Minister John Major, recalled how years later his father (who trod the boards as part of the act ‘Drum and Major’) expressed similar sentiments about Gertie. Her death made the TV and radio news of the time, papers including the Sentinel, carried glowing obituaries to the star and memorials were mooted, though the only one of note at the time was a memorial bench that was unveiled in Edinburgh. In the Potteries memorials to Gertie Gitana have for the most part been fleeting. The Gertie Gitana pub (later The Stage Door) has come and gone, likewise Gitana’s pub in Hartshill and today few save die-hard local historians or music hall enthusiasts remember her. But her name lives on in Gitana Street, an honour that never ceased to delight and surprise her. As her husband Don Ross recalled, on the day she died Gertie was fading away, but talking with him about this and that when unbidden she suddenly brightened up and said, ‘Fancy them naming that street in Hanley after me.’

Source, Google Earth.

*Comedian Roy Hudd in his foreword to Ann Oughton’s biography of Gertie Gitana, recalled asking Don Ross in later years if Gertie really had used the amusing ‘… I think I’ll play my saxophone’ line in Cinderella, but Don neither confirmed nor denied it.

Reference: Ann Oughton, Thanks for the Memory, passim;Ted Ray, Raising the Laughs, pp. 86-87; Evening Sentinel 15 February 1954 .