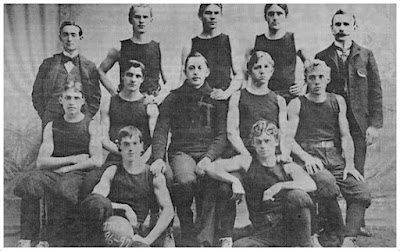

the ball, his friend Al Bratton is bottom right.

In 1896, Frederick Cooper, a distant American cousin of mine, earned himself a place in the history books through the simple act of accepting a fee. Several years earlier, a dynamic new game called basketball had been invented that was gaining a strong following in the various YMCAs on America’s east coast. Fred, already a keen sportsman had like many others quickly warmed to the game, becoming the star player and captain of the highly successful Trenton YMCA team that for the previous three years had dominated the emerging leagues. At first the new game had been played for fun and entertainment, but the groundswell of support soon saw seats being sold for popular teams and inevitably the money trickled back to the players that the crowds wanted to see. The result was that in 1896 Fred was the first to accept payment for a game and in doing so became the world’s first professional basketball player.

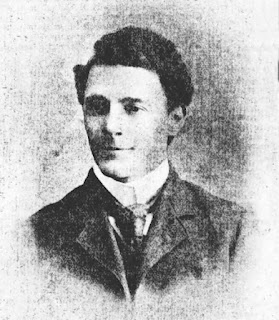

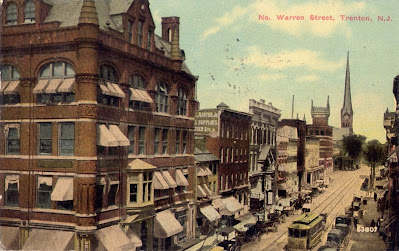

Though he would make his name in the United States, Fred Cooper was actually born at 21 Bethesda Street, Shelton on 25 March 1874, the fifth of seven children – six boys and one girl – born to Thomas Cooper and Ann, nee Simpson. Fred’s father, Thomas, had started out as a working potter but over the years had moved into small scale pottery manufacture. However, in the mid-1880s, in the wake of what was later described in Fred’s obituary as ‘some business reverses’, Thomas and Ann decided to emigrate and join their eldest child, William who was already settled in the States, working at the Greenwood Pottery in Trenton, New Jersey. The Coopers left Britain early in 1886, travelling as steerage passengers (i.e. 3rd class) aboard the SS England, arriving at New York on 27 May 1886, from where they made the relatively short journey south west across the state to Trenton. As it turned out, Thomas would only enjoy his new home in America for a few years, dying in 1891 at the age of 56, but his wife and children settled into their new lives and over time became valued members of the local community.

On arriving in the States, Fred and his younger brother Albert, or ‘Al’ as he became best known, had been enrolled in the Centennial School where they soon got involved in sports and stood out as skilled footballers, a game their father had taught them. Fred especially proved to be an all-round sportsman, also taking up baseball, competitive running and later becoming a fine billiards player and a good bowler. His successes, though were at first eclipsed by his older brother, Arthur, who back in Britain had been such a skilled footballer that in the early to mid 1880s he played for Stoke F.C.’s junior team, Stoke Swifts. Arthur seems to have stayed behind for a year after the rest of the family emigrated, perhaps to help the Swifts in their attempt to win the junior league cup. Once this was over though, in 1887, he too took a ship to the States, but not before being presented with a handsome medallion by his team mates and the club. Once in the States, Arthur’s success had continued, and it was not long before he was picked as a member of the All-America soccer team.

While his brother’s career blossomed, Fred left school and found work as a sanitary-ware presser at one of Trenton’s pot banks, a job he would do for the better part of three decades. He continued to pursue his love of sport in his spare time through the local YMCA, which acted as a youth club for boys and young men of religious families like the Coopers. Here he found a kindred spirit in another keen footballer named Al Bratton, with whom he seems to have formed a winning partnership, not only on the football pitch, but also when the two of them decided to try their hand at the new game of basketball that was sweeping through the YMCA branches. Only a few years had passed since Canadian-born training instructor James Naismith had dreamt up the indoor game to placate a group of YMCA trainees at the School for Christian Workers, Springfield, Massachusetts, who had been chafing at their inactivity during the long winter months. Though rough-hewn at first, with early games resembling pitched battles between oversized teams, basketball proved an immediate hit and when Naismith published an article on the game it was quickly taken up by YMCA branches along America’s east coast. Soon, matches were drawing sizeable crowds and more and more teams sprang up, one of which was Trenton YMCA.

Fred Cooper and Al Bratton first joined the Trenton YMCA basketball team for the 1893-94 season and had an immediate and lasting impact on how the game was played. In those early days, basketball was a game of individual dribblers working their way through the opposition before attempting a shot at the basket, a method that favoured heavy-set players who could push their way through the field. According to one of basketball’s early chroniclers, Cooper and Bratton changed this, creating a more fluid game by drawing on their footballing skills to develop a system of short, swift passes between them on the run, a style of play that completely unbalanced opposing teams.

‘The Trenton system of passing was definite. It meant to carry the ball to the opponent’s basket in order that a goal might be scored, and time and again I have seen Cooper and Bratton in those early days, pass the ball back and forth between them – no one else touching it – and score against all the efforts of the entire opposing team. I have seen them do this trick away from home and witnessed the spectators rise en masse and cheer the brilliant exhibition in spite of the fact that it was being done by invading players.’

For the next three seasons, the Trenton YMCA dominated the game in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania by which time Fred was the team captain and unofficial coach. Despite his refinements to the game, rough play characterised basketball in those free-wheeling and largely unregulated years, with physical injuries being an all too common feature of play, both on and off the court. Not only was there brawling between players, but partisan crowds took whatever opportunities came their way to try and injure or discomfort the rival team and as a result fighting between players and spectators was not unusual. Though the YMCA had quickly lauded Naismith’s new game for promoting a useful spirit of ‘muscular Christianity’ – a healthy body breeding a healthy mind – the rough-housing and unsportsmanlike behaviour drew the Association’s displeasure and increasingly basketball teams deserted the YMCA gyms, or were ousted by outraged officials and had to find other venues to play in.

Such seems to have been the case at the Trenton YMCA. Unspecified ‘trouble in the gymnasium’, followed by a string of disagreements between the branch secretary and the YMCA team saw the basketball players shifting their base to the Masonic Temple, a large building in downtown Trenton. Here the team made use of the large reception room on the top floor, where a 12 feet high mesh fence with gates at either end was built enclosing the court. This ‘cage’ was a new innovation, built to stop the ball going out of play so readily and prevent some of the troubles caused by resultant clashes with spectators. The Trenton team were the first to employ this device and though its use eventually fell out of favour, its early employment coined the term ‘cager’ as a snappy way to refer to a basketball player, a term that is apparently still in use today.

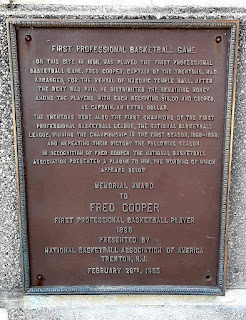

It was in this cage that Fred Cooper and his team mates made history by playing what is presumed to be the first professional basketball game on 7 November 1896, against Brooklyn YMCA. The game had been advertised in a local paper three days earlier (another first) and provisions were made for a sizeable crowd, raised seating being built around the court. Seats were priced at 25c, standing room cost 15c. Nor would the organisers be disappointed by the turn out, ‘a large and fashionable audience’ of 700 turning up to watch.

The Trenton team came out smartly dressed in red sleeveless tops, black knickerbockers and stockings and white ankle shoes. There were seven in each team, two forwards, a centre, two side centres and two defenders. This was before the days of the tall men in basketball, all of them being average sized, Fred himself was only 5 feet, 7 inches tall. In accordance with the practice of the time, the home team supplied the referee and the visitors chose the umpire.

The game started with seven minutes of ‘fierce playing’ before Newt Bugbee, one of Trenton’s side centres scored the first goal. Fred did not disappoint either, leading the scoring by gaining six points for three baskets, while a player named Simonson scored Brooklyn’s only point with a free throw three minutes before the game finished. Trenton’s team played the full 40 minutes, while Brooklyn had one substitution. The final score was a 16-1 victory for Trenton.

Following the game, Trenton’s manager hosted a supper for both teams at the Alhambra Restaurant, where the Trenton players received their historic payment. There has been some disputing the amount actually paid to the players after the various expenses were deducted, but the accepted version of events was that quoted in Fred’s obituary in 1955. ‘All the players collected $15 each, but Fred Cooper was the captain and manager (sic) and was paid off first. Thus he became the first professional basketball player in the world. He was proud of this distinction all his life.’

Many versions of the story add that Fred as the captain was also paid a dollar more than his compatriots, which if true also made him the game’s first highest paid player. Also, the ‘professional’ status is perhaps somewhat fuzzy as he still worked as a potter; semi-professional, might be more accurate. That argument aside, it started a trend that would lead to the fully professional game seen today.

As they had with the new swift style of play and Trenton’s ‘cage’, other teams quickly followed Trenton down the professional route. This in turn led to the formation in 1898 of the first professional league, the National Basketball League, which Trenton under Fred Cooper’s captaincy promptly dominated, winning the first two NBL titles. By this time the team had been joined by Fred’s younger brother, Albert. Tall and handsome and as skilled as his brother, Al Cooper proved to be an accomplished goal scorer and easily the best player in the new league.

Despite their successes, during the first few NBL seasons, Fred was growing disillusioned with the Trenton team. His brother Al and Harry Stout, Trenton’s top scorer did not get along, while the team’s co-owners had also had a falling out. Keen for a fresh start, at the beginning of the 1900-1901 season, he quit the Trenton squad to coach a new team in nearby Burlington. The result, though, was embarrassing. Though Fred was an excellent coach, his new team lacked Trenton’s pool of of talented players, the result being that Burlington lost its first eight games before Fred gave up. He was immediately snapped up to coach the Bristol team, before going on to coach at Princeton University between 1904-1906. It was not until 1910 that Fred returned to coach the struggling Trenton Eastern Basketball League team and did so successfully, winning the EBL title the following year. He was replaced as the coach the next year, but returned to coach Trenton one more time ten years later. His last stint as a team coach was at Rider College in the 1920s.

Thomas and Mabel.

Photo courtesy of Susan Corrigan.

Alongside his sporting career, Fred enjoyed a happy family and social life. In 1901, he had married Catherine Carr and the couple had three children. Like his siblings he was an active member of the Trenton community, becoming in time a church elder, and a member of various local and national patriotic orders and Masonic lodges. As noted earlier he had worked for many years as a sanitary-ware presser at the Enterprise Pottery, which generously allowed him time off for his coaching duties, but he quit his job in 1922, when on the strength of his sporting career, he was offered a position as a director of local sports grounds, a posting that eventually led to him becoming head of the city recreation department.

Fred Cooper died in January 1955 at the age of 80, being buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Trenton. The local paper gave him a fulsome obituary, while the National Basketball Association, heir to the early leagues that Fred and others had helped to forge, did not forget its pioneering sportsman. In February 1955, the NBA presented the city of Trenton with a bronze plaque in honour of Fred and his ground-breaking professional match, which was placed on the site of Trenton’s old Masonic Temple.

Photo courtesy of Grace Cooper

Reference: Robert W. Peterson, Cages to Jump Shots: Pro Basketball’s Early Years (New York, 1990) pp. 32-37. Obituary, Trenton Evening Times, 7 January 1955.

Family information courtesy of Grace Cooper and Susan Corrigan.

Website: Pro Basketball Encyclopedia.